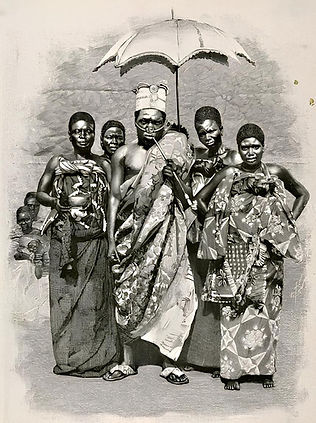

Agoli-agbo

King of Dahomey

Agoli-agbo is considered to have been the twelfth and final King of Dahomey. He was in power from 1894 to 1900. He took the throne after the previous king, Béhanzin, went into exile after being defeated in the invasion of Dahomey by France in the Second Franco-Dahomean War. The exile of Béhanzin did not legalize the French colonization. The French general Alfred-Amédée Dodds offered the throne to every one of the immediate royal family, in return for a signature on a treaty establishing a French protectorate over the Kingdom; all refused. Finally, on January 15, 1894, Béhanzin's Army Chief of Staff Prince Agoli-agbo (whose name meaning "the dynasty has not fallen"), brother of Béhanzin and son of King Glélé, signed. He was appointed to the throne, as a 'traditional chief' rather than head of state of a sovereign nation, by the French when he agreed to sign the instrument of surrender. He 'reigned' for only six years, assisted by a French Viceroy. The French prepared for direct administration, which they achieved on 12 February 1900. As the Indigénat exacerbated the exploitation, Agoli-agbo went into exile in Gabon. In 1910, he was allowed to return and to live in the Save Region. He occasionally returned to Abomey in order to perform ancestor worship for the departed kings. Agoli-agbo's symbols are a leg kicking a rock, a bow (a symbol of the return to

traditional weapons under the new rules established by the colonial administrators), and a broom, and the last king of Dahomey.

The military of the Kingdom of Dahomey was divided into two units: the right and the left. The right was controlled by the migan and the left was controlled by the mehu. At least by the time of Agaja, the kingdom had developed a standing army that remained encamped wherever the king was. Soldiers in the army were recruited as young as seven or eight years old, initially serving as shield carriers for regular soldiers. After years of apprenticeship and military experience, they were allowed to join the army as regular soldiers. To further incentivize the soldiers, each soldier received bonuses paid in cowry shells for each enemy they killed or captured in battle. This combination of lifelong military experience and monetary incentives resulted in a cohesive, well-disciplined military. One European said Agaja's standing army consisted of "elite troops, brave and well-disciplined, led by a prince full of valor and prudence, supported by a staff of experienced officers". The army consisted of 15,000 personnel which was divided into right, left, center and reserve; and in each of these was further divided into companies and platoons. In addition to being well trained, the Dahomey army under Agaja was also very well armed. The Dahomey army favored imported European weapons as opposed to traditional weapons. For example, they used European flintlock muskets in long-range combat and

imported steel swords and cutlasses in close combat. The Dahomey army also possessed twenty-five cannons. By the late 19th century, Dahomey had a large arsenal of weapons. These included the Chassepot Dreyse, Mauser, Snider Enfield, Wanzel, Werndl, Peabody action, Winchester, Spencer, Albini, Robert Jones carbine, French musketoon 1882 and the Mitrailleuse Reffye 1867. Along with firearms, Dahomey employed mortars. When going into battle, the king would take a secondary position to the field commander with the reason given that if any spirit were to punish the commander for decisions it should not be the king. Dahomey units were drilled constantly. They fired on command, employed countermarch, and formed extended lines from deep columns. Tactics such as covering fire, frontal attacks and flanking movements were used in the warfare of Dahomey. The Dahomey Amazons, a unit of all-female soldiers, is one of the most unusual aspects of the military of the kingdom. Unlike other regional powers, the military of Dahomey did not have a significant cavalry (like the Oyo empire) or naval power (which prevented expansion along the coast). From the 18th century, the state could obtain naval support from Ardra where they had created a subordinate dynasty after conquering the state in the early 18th century. Dahomey enlisted the services of Ardra's navy against the Epe in 1778 and Badagry in 1783. The Dahomean state became widely known for its corps of female soldiers. Their origins are debated; they may have formed from a palace guard or from gbetos (female hunting teams). They were organized around 1729 to fill out the army and make it look larger in battle, armed only with banners. The women reportedly behaved so courageously they became a permanent corps. In the beginning, the soldiers were criminals pressed into service rather than death. Eventually, the corps was respected enough that King Ghezo ordered every family to send him their daughters, with the fittest being chosen as soldiers. European accounts clarified that seven distinct movements were required to load a Dane gun which took an Amazon 30 seconds in comparison to the 50 seconds it took a Dahomean male soldier to load.

The King of Dahomey (Ahosu in the Fon language) was the ruler of Dahomey, a West African kingdom in the southern part of present-day Benin, which lasted from 1600 until 1900 when the French Third Republic abolished the political authority of the Kingdom. The rulers served a prominent position in Fon ancestor worship leading the Annual Customs and this important position caused the French to bring back the exiled king of Dahomey for ceremonial purposes in 1910. The Palace and seat of government were in the town of Abomey. Early historiography of the King of Dahomey presented them as absolute rulers who formally owned all property and people of the kingdom. However, recent histories have emphasized that there was significant political contestation limiting the power of the king and that there was a female ruler of Dahomey, Hangbe, who was largely written out of early histories. Multiple lists of the kings of Dahomey have been put together and many of them start at different points for the first King of Dahomey. In various sources, Do-Aklin, Dakodonu, or Houegbadja are all considered the first king of Dahomey. Oral tradition contends that Do-Aklin moved from Allada to the Abomey plateau, Dakodonu created the first settlement and founded the kingdom (but is often considered a "mere chief"), and Houegbadja who settled the kingdom, built the palace and created much of the structure is often considered

the first king of Dahomey. Oral tradition contends that the kings were all of the Aladaxonou dynasty, a name claiming descent from the city of Allada which Dahomey conquered in the 1700s. Historians largely believe now that this connection was created to legitimate rule over the city of Allada and that connections to the royal family in Allada were likely of a limited nature. In oral tradition of most accounts, Houegbadja is considered the first king and recognition of him happened first in the Annual Customs of Dahomey. The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. It developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a regional power in the 18th century by expanding south to conquer key cities like Whydah belonging to the Kingdom of Whydah on the Atlantic coast which granted it unhindered access to the tricontinental Atlantic Slave Trade. For much of the middle 19th century, the Kingdom of Dahomey became a key regional state, after eventually ending tributary status to the Oyo Empire. European visitors extensively documented the kingdom, and it became one of the most familiar African nations known to Europeans. The Kingdom of Dahomey was an important regional power that had an organized domestic economy built on conquest and slave labor, significant international trade and diplomatic relations with Europeans, a centralized administration, taxation systems, and an organized military. Notable in the kingdom were significant artwork, an all-female military unit called the Dahomey Amazons by European observers, and the elaborate religious practices of Vodun. The growth of Dahomey coincided with the growth of the Atlantic slave trade, and it became known to Europeans as a major supplier of slaves. Dahomey was a highly militaristic society constantly organised for warfare; it engaged in wars and raids against neighboring nations and sold captives into the Atlantic slave trade in exchange for European goods such as rifles, gunpowder, fabrics, cowrie shells, tobacco, pipes, and alcohol. Other captives became slaves in Dahomey, where they worked on royal plantations or were killed in human sacrifices during the festival celebrations known as the Annual Customs of Dahomey. The Annual Customs of Dahomey involved significant collection and distribution of gifts and tribute, religious Vodun ceremonies, military parades, and discussions by dignitaries about the future for the kingdom. In the 1840s, Dahomey began to face decline with British pressure to abolish the slave trade, which included the British Royal Navy imposing a naval blockade against the kingdom and enforcing anti-slavery patrols near its coast. Dahomey was also weakened after failing to invade and capture slaves in Abeokuta, a Yoruba city-state which was founded by the Oyo Empire refugees migrating southward. Dahomey later began experiencing territorial disputes with France which led to the war in 1890 and part of the kingdom becoming a French protectorate. The kingdom fell four years later, when renewed fighting resulted in the last king, Béhanzin, to be overthrown and the country annexed into French West Africa.

Awards: Insignia, sash and star of the Order of the Black Star (Ordre de l'Étoile Noire).